Why do great male artists, especially those pre-World War 2, far outnumber the women? It took courage for a woman to be independent and practice a profession in her own right - a woman's rightful place in society was to be dependent upon and obedient to her father, until that role was taken over by her husband. Who knows how many potential great talents were lost to the world because they were females and kept in "their place"?

Nevertheless, there have been some outstanding women artists, going right back from modern times to Artemisia Gentileschi and Sofonisba Anguissola in the sixteenth century.

Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807) was fortunate in having a father, the Swiss painter Joseph Johann Kauffmann, who encouraged her burgeoning talent. Her mother died when she was very young, and she accompanied her father on his travels in Austria and Italy. He allowed her to assist him by painting the backgrounds of his works, but she received her first commission at the age of 13, and soon established a reputation in her own right.

She was a child prodigy - spoke Italian, French and English as well as her native German and she was also musically talented. She played several instruments and had an exceptionally sweet singing voice. Her painting was greatly admired, but she was an attractive girl and enjoyed great personal popularity as well.

She travelled extensively in Italy, spending long periods in Rome, Venice and Milan. She preferred to paint historical and mythological subjects, which was considered to be the only important artistic genre, and did so in a neo-classical style.

However, she was much in demand among the upper crust as a portraitist.Her portrait of the influential German archaeologist and art historian Winckelmann was greatly admired, not least by the sitter, and led to a plethora of commissions. In Venice, she was befriended by Lady Wentworth, the wife of the English ambassador. Lady Wentworth persuaded Angelica to go to London with her, where she was very well received in Society, and became a favourite of the royal family.

One of the first portraits she painted in London was of the actor David Garrick, which was exhibited at "Mr Moreing's great room in Maiden Lane."

Sir Joshua Reynolds, who called her "Miss Angel", was a good friend, and they painted portraits of each other. Under his auspices, she was one of the founder members in 1768 of the Royal Academy, an institution then not famous for welcoming female members. She was one of the artists appointed by the Academy to decorate St Paul's Cathedral and also the Academy's lecture room at Somerset House.

In her early twenties, she was duped into marrying a con man who pretended to be a Swedish count, but Reynolds helped her to obtain a legal separation. When the spurious Count died in 1781, she married Antonio Zucchi, a Venetian artist, and went to live with him in Rome. She was widowed after fifteen happy years of marriage, but continued to work and to enjoy great prestige.

When she died in Rome at age 43, her splendid funeral was directed by Canova. The entire Academy of St Luke, plus all the celebrities of the day, followed her to her tomb and some of her best pictures were carried in the procession.

Her work has not really stood the test of time - the neo-classical works are regarded as sentimental and her portraits are considered to lack variety and expression. However, her works are still exhibited in the collections of many of the world's top museums, among others the National Gallery in London, the Hermitage, the Uffizi and the Alte Pinothek in Munich.

Tuesday, 29 March 2011

The Art Lover as Couch Potato

Recently, I recommended some documentary DVDs on art and artists, but because Marcia keeps me on a short leash, I had no room then to talk about some of my favourite biopics. So let's take a look at a few of those movies - are you sitting comfortably? Then I'll begin:

Many of our older members will fondly remember those two popular dramas of yesteryear, Lust for Life (1956) and The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) which dealt with Van Gogh and Michelangelo respectively.

Lust for Life starred Kirk Douglas as Vincent: a remarkable performance that netted him an Oscar nomination. He even looked like Vincent! Sadly, and to my mind unfairly, he was pipped at the post by Yul Brynner for The King and I. However, Anthony Quinn, who played Vincent's friend Paul Gauguin, did get an Oscar for his supporting role.

Lust for Life was filmed largely on location in France and is noted for its beautiful cinematography. Several art museums kindly allowed original works in their collections to be photographed. These, in addition to copies that were painted by Robert Parker, depicted Vincent's canvases in the movie. Altogether a beautiful and well-reasearched film.

The Agony and The Ecstasy, starring Charlton Heston as Micelangelo, is based on the eponymous novel by Irving Stone. Its focus is the stormy relationship between the artist and Pope Julius II, who commisssioned him to paint the Sistine chapel ceiling. Rex Harrison, fresh from My Fair Lady, played the Pope. My brain kept superimposing Raphael's sublime portrait of Julius II on the Harrison features. I didn't want to see Professor Higgins in a red robe discussing theology and art with Michelangelo.

The sets of the Papal and the Medici palaces are lavish and the costumes are beautiful - one gets a real sense of what Rome was like in the 16th century. I learnt a lot about the technique of fresco painting, too!

Still in Rome, we turn to Derek Jarman's Caravaggio. Derek Jarman requires a strong stomach at the best of times: he never shrinks from depicting the sordid details. The life and times of Caravaggio gave him lots of scope: sex, violence, crime, art, corruption - all grist to his mill. The central theme is Caravaggio's relationship with the urchin Ranuccio (Sean Bean) and the prostitute Lena (Tilda Swinton), who were his models and lovers. Jarman uses dramatic chiaruscuro lighting, so that the whole movie looks like Carvaggio's paintings and indeed recreates many of the famous works as tableaux vivants.

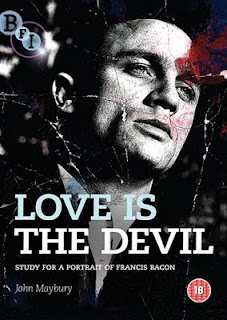

I recently saw Love is the Devil, directed by John Maybury, with Derek Jacobi giving a memorable and disturbing performance as Francis Bacon. Daniel Craig plays George Dyer, who came to burgle Bacon's apartment and stayed to become his lover, model and muse. Tilda Swinton, fresh from playing a prostitute in Caravaggio, puts in a creditable turn as the barmaid at Bacon's favourite pub, where he consorts with his dodgy friends.

The film is dark and unsettling, like Bacon's paintings. The artist's estate refused permission for any of Bacon's paintings to be shown in the film, but, as in the Caravaggio film, several scenes are recognisable as Bacon paintings. There are also other echoes of his work: Jacobi is often seen preening in a triple mirror, echoing the triptyches Bacon likes to paint; Maybury uses odd camera angles and distorted views to give the film the Francis Bacon look.

Pollock, directed by its star Ed Harris, tells the story of Jackson Pollock's last years, from his meeting with his future wife, painter Lee Krasner, until his death in a car accident at the age of 44.

Ed Harris devoted years to this project and learned to turn out credible drip paintings, almost indistinguishable from Pollock's own work. Harris, who bears a remarkable physical resemblance to the artist, convincingly depicts Pollock's struggle with depression and alcoholism and the passionate way he painted. This film left me with a new appreciation and understanding of the Pollock oeuvre!

But enough of the sordid tales of Caravaggio, Bacon and Pollock - let's have a look at the tranquil world of Jan Vermeer. Tracy Chevalier's novel The Girl With the Pearl Earring was beautifully filmed by Peter Webber in 2003 and the DVD is well worth another look even if you saw it on the big screen at the time.

What could be more delightful than the luminous Scarlett Johansson and the elegant Colin Firth (who, to me, will always have a whiff of Mr Darcy about him.) Every shot in the film has the Vermeer look and I was charmed by the scenes of Delft, a lovely town that looks today exactly as it did when Vermeer walked its cobbled streets.

Peter Greenaway's Nightwatching is an intriguing fictionalised account of the creation of The Night Watch by Rembrandt. Greenaway posits a fascinating conspiracy theory involving murder, rape and corruption among the leading Amsterdam families. Faintly echoing Dan Brown, he points out coded references to the conspiracy in each of the 34 characters depicted in the painting.

The film goes on to trace the downturn in Rembrandt's fortunes, leading to his eventual bankruptcy and death, all as a result of revenge by the aristos whose peccadilloes were revealed by the artist in his great painting.

Many of our older members will fondly remember those two popular dramas of yesteryear, Lust for Life (1956) and The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) which dealt with Van Gogh and Michelangelo respectively.

Lust for Life starred Kirk Douglas as Vincent: a remarkable performance that netted him an Oscar nomination. He even looked like Vincent! Sadly, and to my mind unfairly, he was pipped at the post by Yul Brynner for The King and I. However, Anthony Quinn, who played Vincent's friend Paul Gauguin, did get an Oscar for his supporting role.

Lust for Life was filmed largely on location in France and is noted for its beautiful cinematography. Several art museums kindly allowed original works in their collections to be photographed. These, in addition to copies that were painted by Robert Parker, depicted Vincent's canvases in the movie. Altogether a beautiful and well-reasearched film.

The Agony and The Ecstasy, starring Charlton Heston as Micelangelo, is based on the eponymous novel by Irving Stone. Its focus is the stormy relationship between the artist and Pope Julius II, who commisssioned him to paint the Sistine chapel ceiling. Rex Harrison, fresh from My Fair Lady, played the Pope. My brain kept superimposing Raphael's sublime portrait of Julius II on the Harrison features. I didn't want to see Professor Higgins in a red robe discussing theology and art with Michelangelo.

The sets of the Papal and the Medici palaces are lavish and the costumes are beautiful - one gets a real sense of what Rome was like in the 16th century. I learnt a lot about the technique of fresco painting, too!

Still in Rome, we turn to Derek Jarman's Caravaggio. Derek Jarman requires a strong stomach at the best of times: he never shrinks from depicting the sordid details. The life and times of Caravaggio gave him lots of scope: sex, violence, crime, art, corruption - all grist to his mill. The central theme is Caravaggio's relationship with the urchin Ranuccio (Sean Bean) and the prostitute Lena (Tilda Swinton), who were his models and lovers. Jarman uses dramatic chiaruscuro lighting, so that the whole movie looks like Carvaggio's paintings and indeed recreates many of the famous works as tableaux vivants.

I recently saw Love is the Devil, directed by John Maybury, with Derek Jacobi giving a memorable and disturbing performance as Francis Bacon. Daniel Craig plays George Dyer, who came to burgle Bacon's apartment and stayed to become his lover, model and muse. Tilda Swinton, fresh from playing a prostitute in Caravaggio, puts in a creditable turn as the barmaid at Bacon's favourite pub, where he consorts with his dodgy friends.

The film is dark and unsettling, like Bacon's paintings. The artist's estate refused permission for any of Bacon's paintings to be shown in the film, but, as in the Caravaggio film, several scenes are recognisable as Bacon paintings. There are also other echoes of his work: Jacobi is often seen preening in a triple mirror, echoing the triptyches Bacon likes to paint; Maybury uses odd camera angles and distorted views to give the film the Francis Bacon look.

Pollock, directed by its star Ed Harris, tells the story of Jackson Pollock's last years, from his meeting with his future wife, painter Lee Krasner, until his death in a car accident at the age of 44.

Ed Harris devoted years to this project and learned to turn out credible drip paintings, almost indistinguishable from Pollock's own work. Harris, who bears a remarkable physical resemblance to the artist, convincingly depicts Pollock's struggle with depression and alcoholism and the passionate way he painted. This film left me with a new appreciation and understanding of the Pollock oeuvre!

But enough of the sordid tales of Caravaggio, Bacon and Pollock - let's have a look at the tranquil world of Jan Vermeer. Tracy Chevalier's novel The Girl With the Pearl Earring was beautifully filmed by Peter Webber in 2003 and the DVD is well worth another look even if you saw it on the big screen at the time.

What could be more delightful than the luminous Scarlett Johansson and the elegant Colin Firth (who, to me, will always have a whiff of Mr Darcy about him.) Every shot in the film has the Vermeer look and I was charmed by the scenes of Delft, a lovely town that looks today exactly as it did when Vermeer walked its cobbled streets.

Peter Greenaway's Nightwatching is an intriguing fictionalised account of the creation of The Night Watch by Rembrandt. Greenaway posits a fascinating conspiracy theory involving murder, rape and corruption among the leading Amsterdam families. Faintly echoing Dan Brown, he points out coded references to the conspiracy in each of the 34 characters depicted in the painting.

The film goes on to trace the downturn in Rembrandt's fortunes, leading to his eventual bankruptcy and death, all as a result of revenge by the aristos whose peccadilloes were revealed by the artist in his great painting.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)