There is still time to see the marvellous Francis Bacon exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW! I made the pilgrimage to Sydney before Christmas and was richly rewarded for my effort.

Francis Bacon was a very prolific painter (one has to wonder how he found the time to ghost-write all Shakespeare's plays for him, not to mention the sonnets.)

There are more than fifty of his major works on show, including a number of the iconic triptychs. The scope of the exhibition covers the development of his career through five decades. We have not been fobbed of with minor works - these paintings have been sourced from major collections, including those of the Tate in London and MOMA in New York. I also saw an old friend: the NGV's "Study from the Human Body", which our members will know.

|

| "Study From the Human Body", in the NGV, Melbourne |

The exhibition includes many portraits, mainly of friends and lovers, but there is also one of the "Screaming Pope" series of Pope Innocent X, after the Velasquez portrait that obsessed Bacon.

|

| Pope Innocent X by Velasquez, and Bacon's Screaming Pope |

That screaming mouth appears in many of his works - I was interested to read recently that Bacon was fascinated with Sergei Eisenstein's "Battleship Potemkin" and that he constantly reproduced the open-mouthed scream of the injured nurse with the runaway pram on the Odessa Steps.

|

| Screaming nurse from Battleship Potemkin |

The various elements of that scene on the Odessa Steps have been referenced in so many films, paintings and novels that Eisenstein would have been a millionaire, had he received royalties. To my mind, Battleship Potemkin should rank above Citizen Kane in the All-Time Great Movies list. But I digress, we are not here to do film reviews.

|

| Portrait of Lucian Freud |

Bacon and his friend Lucien Freud painted each other many times, and there was indeed a portrait of Freud on show, but I thought it didn't look a lot like him. When I read the wall text, I saw why. Lucien Freud didn't actually sit for this portrait, Bacon painted it from a photograph. Couldn't be bothered to hunt up a photo of Freud, so he just used one of Franz Kafka that happened to be handy. (I'm planning to commission Agata to paint my portrait, as soon as I can find a good photo of Elle MacPherson.)

|

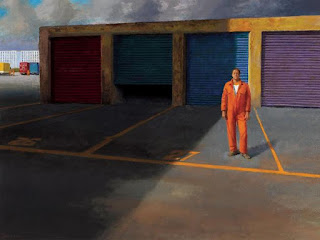

| George Dyer's death |

Bacon's violent, drug-and-alcohol-addicted lover George Dyer was the subject of several works in the exhibition, including one of the harrowing triptychs Bacon painted after Dyer's death in a hotel room in Paris. The life force leaking out of his contorted figure forms pink, amoeba-like puddles on the floor. (Another of those post-mortem triptychs, depicting Dyer writhing in agony on a beach, was sold in 2008 at Christies for $44 million.)

|

| Photo of Henrietta Moraes, from FB's studio, and the painting from it. |

I particularly liked a nude of Henrietta Moraes, a rather louche model and muse for several leading British painters of the Fifties. Lucien Freud, with whom she had a torrid affaire, painted three portraits of her and Bacon painted her at least a dozen times. This picture shows her lying on a rumpled bed, seemingly tipsy and exuding an air of sexual invitation. For a man with a gay S&M lifestyle, Bacon certainly managed to infuse his portraits of women with a lot of highly charged sexuality.

Most interesting was a row of vitrines displaying photographs of Bacon's chaotic studio, and some of its contents: references that he used for his work, including medical texts featuring horrible disfigurements and skin diseases, magazine clippings, newspaper cuttings and photographs that he used when painting portraits, all crumpled and paint-spattered, the better to contort the faces he was painting.

|

| Self portrait |

Bacon is not for the faint-hearted. His paintings are dark and disturbing, with a visceral beauty that fascinates even as it repels. Those who can look past the brutally distorted images and be receptive to the raw emotion in his vibrant and powerful paintings, will enjoy a very satisfying experience.